An Actionable and Realistic Framework For Core Training

This blog tackles one of the most misunderstood components of the musculoskeletal system. It sits at the intersection of discourse around aesthetics, performance, and health. Because of this, the principles surrounding its training have been so heavily distorted by marketing campaigns and social pressures. This blog discusses the core, beyond the myths and moralization. I’ll reverse-engineer current thought-systems surrounding core training, discuss how to train the core properly, how current core training dogma is flawed, and try to answer a series of questions that can help you perform better, prevent injury, and enrich your understanding of training.

The Beginner’s Understanding of The Core: Visual Abs

We’ll begin this blog as most begin to understand the core, as ‘abs’. Having visible abs definition has been unjustly moralized, framed as a proxy marker for discipline and health, despite having little to do with any of those in isolation. For decades, this moralization has been leveraged to sell insecurity-driven programming, gimmicky workouts, and endless variations of high-repetition ‘ab-circuits’ that promise results they cannot physiologically deliver. Since the rise of modern fitness culture, abdominal workouts have primarily been advertised using an aesthetic focus. The ‘Sleek and Slim’ core DVDs of the 80s and 90s, the ‘6-pack shortcut’ videos of the early 2000s and 2010s, and the ‘boxy-to-snatched' waist YouTube workouts of the 2010s and 2020s. In my experience as a personal trainer, online fitness coach, and clinical exercise physiologist, I quickly learned the entry-level understanding of core training for most was crunches = abs.

Taking on decades of marketing is a lot for one blog! But I believe it’s possible by hopefully providing a clear, science-based framework for understanding what the core is, what is does, and how it should be trained if your goals include performance, longevity, injury prevention, pain management, or muscular development. The goal is to not demonize any exercise, but to replace vague rules and dogma with principles grounded in exercise physiology. I’m not going to ask you to restructure your goals and entire way of thinking, but I am asking you to keep an open mind to there being many ways of thinking about training concepts. The more ways of thinking you open your mind to, the more resilient your training decisions will become when faced with adversity.

What Is The Core and What Does it Do?

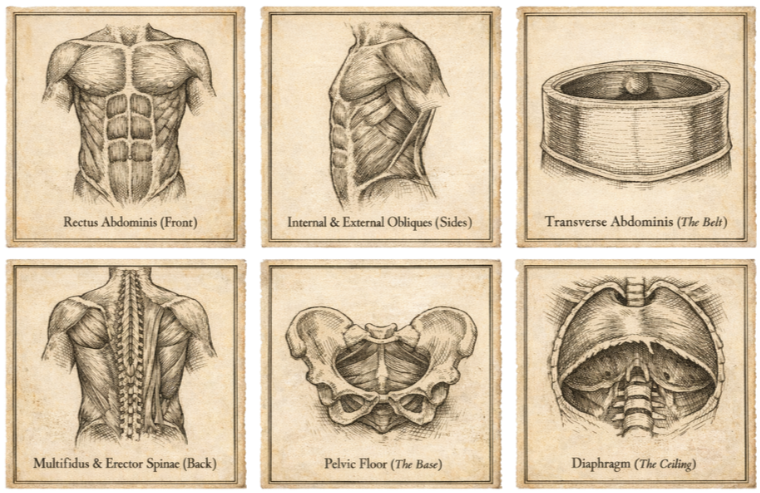

The term “core” is often used loosely, but anatomically it refers to a group of muscles that surround, stabilize, and coordinate movement in the trunk and pelvis. These include, but are not limited to, the rectus abdominis (front), internal and external obliques (sides), transversus abdominis (belt that wraps around), multifidus, erector spinae (back), pelvic floor (the base) and the diaphragm (ceiling). On the left, you’ll see a diagram generated by ChatGPT to help visualize these muscles.

Functionally, the core has many roles in human movement. These include breathing, continence, childbirth, excretion, organ protection, spinal support for posture and balance, trunk mobility (spinal movement), and force transfer (1,2,3,4). In this blog, I will focus primarily on the core’s uses in being a force-transmitter between the lower and upper body through abdominal pressure regulation, as well as it’s role in spinal control and stability. I will be excluding targeted pelvic floor and diaphragm work as it is outside of the scope of this blog. Spinal erectors will be included, but you will notice direct erector training isn’t included in many images. This is due to the spinal erectors being trained heavily as a secondary muslce in movements like squats, deadlifts, and rows. However, first understanding these primary biological functions is essential if you want to strengthen the core optimally.

The point of outlining this is to emphasize that the core is not a single muscle group responsible for visible abdominal definition. It’s responsible for so much more in your life. Give it some credit! Even outside of the gym, the core is involved in any task that requires carrying, twisting, or maintaining posture. Another selling point is that while no exercise can “injury proof” the body, improved trunk strength and control are associated with reduced risk of certain low back injuries, especially paired with progressive exposure to load and movement variability (5,6). Despite all the wonderful reasons to train the core, media has successfully reduced the core to a muscle with one function it isn’t responsible for: getting a smaller waist.

Rethinking How Core Training Contributes to Health and Body Composition

Sitting here and telling readers to rethink something they’ve been told for years is a big ask. So, before your brain turns on its pitchforks, there are parts of this conversation I don’t disagree with.

There is substantial evidence showing that waist circumference, on a population level, is a validated proxy marker for visceral adiposity, which is associated with disease risk, though it is not a direct cause (7,8). I am also not here to argue that building muscles or changing your body composition are invalid goals. They are measurable, meaningful, and can have a significant impact on your health (9). I’m a bodybuilder after all; body composition change is my bread and butter. Now that that’s clear, we can move into a more nuanced discussion.

The core, like the rest of the body, contains both lean tissue (muscle, bone, etc.) and non-lean tissue (adipose). This distinction is crucial. Resistance training triggers adaptation in lean tissue. It does not directly reduce non-lean tissue. This means that abdominal exercises can increase core strength or hypertrophy but will not inherently reduce abdominal fat directly. Changes in fat distribution are driven primarily by genetics, dietary quality, environmental factors, psychosocial factors, and hormonal factors, not by localized muscle activation (10,11).

Understanding this distinction immediately eliminates the idea that doing more abdominal exercise leads to a leaner midsection. Spot reduction has been repeatedly disproven in scientific literature, yet it remains in popular fitness culture.

If someone’s goal is to change their body composition or develop strength for longevity or performance, it makes sense they would aim for total body strength. Especially for those with a busy schedule who are targeted by short, ‘quick fix’ abdominal workouts. This doesn’t mean isolated or bodyweight core work has no place, but when time is a limited resource, large multi-joint movements should take priority over isolated core work. If I personally had a limited amount of time to spend training, I would be picking a press, pull, hinge, squat and core movement, not spending all my precious time training my core in isolation.

Below are examples of hinge and squat patterns where the core is used as a force transmitter to train large muscle groups.

Because the core functions as a force transmitter, strengthening it contributes indirectly to increasing total body lean mass by improving the ability to perform these multi-joint movements. However, total body lean mass has a much larger influence on disease risk, health outcomes, and body composition than core strength independently (12). Therefore, training the core should be done not only with the goal of improving it in isolation, but with the intention of building its capacity to act within the movements that will contribute more substantially to your workout's effectiveness and ultimately drive more meaningful long-term improvements.

Where Most Core Training Fails

Many core workouts and core-centered programs fail not because the exercises are useless or inherently flawed. As you’ll see later in this blog, many of the exercises can be useful if given to the right person at the right time. It’s also not because of the lack of equipment or the setting. In fact, this is the main strength of these types of workouts. Being able to do most of your exercise at home with minimal equipment is a great way to reduce the barrier to entry or scale into class-style workouts with more social accountability from other participants. You’ll see plenty of exercises that can be done at home with minimal equipment throughout this blog.

Below are some movements that train the core with minimal equiptment (lying abdominal crunch, quadruped birddog)

I personally believe where these core workouts fail the participant is because they lack an evolving training logic, or they are prioritized over more productive movements.

A common assumption made not just with core training, but especially with core training, is that muscular ‘burn’ or local pain equates effective training. This burning sensation can be a part of effective training; it’s just not the goal. This assumption leads to workouts that are built around constant discomfort, high repetition, and low load (usually bodyweight exercises like crunches and bicycle kicks). While these workouts can cause meaningful adaptation in beginners or actively teach them how to feel and therefore control their core, there may be better options. However, for advanced trainees, the movements included are generally much more difficult to create enough mechanical tension in a way that’s practical to drive meaningful strength or hypertrophy adaptations. Additionally, movements like crunches and bicycle kicks are great for teaching basic bracing and core proprioception but may need to be progressed to develop skills that transfer better to the compound lifts.

If this training logic was applied to other muscle groups, it would be quickly flagged as unreasonable. Not many people who have experience in resistance training would recommend building the glutes with 100 unweighted glute bridges with a very short range of motion. They could start with this but eventually should transition to a movement that is easier to overload and has a larger range of motion like a hip thrust. Yet, abdominal muscles are often an exception, despite being subject to the same physiological principles.

Muscle adapts in response to progressive overload, sufficient volume per week, and adequate proximity to failure. For most individuals, this means training with sets that fall somewhere between 5 and 30 repetitions, performed with enough resistance and control to challenge the tissue meaningfully. Therefore, if one can reach close enough to failure within 30 repetitions with a bodyweight core exercise, this is likely sufficient to serve abdominal hypertrophy (this is why crunches and bicycle kicks aren’t the culprit here). But there are other adaptations that core training can meaningfully contribute to.

How to Train the Core in Isolation: Like Any Other Muscle

If your goal is to strengthen the core musculature, the solution is surprisingly simple: train it like any other muscle.

Although training the core in isolation is inherently narrow-minded when compared to its function, it may have been used in certain programs. If it is to be trained in isolation, the following principles can be followed.

Frequency

Most individuals benefit from training at the core more than once per week. Two to three sessions (either standalone or integrated into other workouts) are sufficient for everyone from recreational to competitive lifters.

Load and Range of Motion

The core can produce and resist significant force. It has been well described in the literature that exercises that use a large range of motion while being controlled and allow for progressive loading are particularly effective for hypertrophy and strength (13). However, the core must balance this with the consideration that discs don’t adapt like other structures in the body, and loading the spine excessively in extreme ranges of motion may place someone at unnecessary risk. So, although an area of contention in physio circles, this includes movements involving spinal flexion and extension when paired with appropriate technique, balanced with other movement patterns, and without existing complications (14, 15).

Intensity and Effort

Sets need to be taken close enough to failure to generate high mechanical tension. This does not require maximal loading, but it does require very intentional effort. Because of the cores' small safe range of motion, it can be difficult to detect a slowing of contraction velocity. It is also very easy to compensate and break techniques when performing core movements. Therefore, intensity may be difficult to self-measure, and tracking load or other training variables may be more useful to ensure consistent progression.

For more information on sets, reps, and intensity for training hypertrophy, check out this blog

Below is an example of an exercise that uses a large range of motion and can be progressively overloaded (loaded decline abdominal crunch & sit-up)

The Unique Role of the Core: Bracing, Transmitting, Resisting, and Stabilizing

While the core can be trained directly, it is unique that most of its functions emerge during complex, multi-joint, and whole-body tasks.

The core rarely acts in isolation during real world activities. Instead, it functions as a stabilizer and coordinator, resisting unwanted motions and force loss while transmitting force to coordinate lower and upper body movement, or stabilizing the spine to allow movement to occur in other areas like the hips, shoulders, knees, and elbows. This is where traditional flexion exercises fall short if they are the only form of training being performed.

To address this, exercises should be rotated that include ways of challenging the core through motion and resisting motion. These qualities are not mutually exclusive from the isolated hypertrophy work, but they serve different purposes and complement one another in the long-term training continuum.

Below are three movements that challenge the core by creating forces it must resist (high plank shoulder tap, low plank birddog, standing Paloff press).

These exercises can range from the simplistic (yet challenging) dead bug or farmers carry, all the way to something more complex such as a contralaterally-loaded suitcase reverse lunge with knee drive. Although seemingly different levels of complexity, these really serve similar purposes. They both challenge the cores' ability to stay rigid while other joints move and control load, a skill that carries over into the larger compound movements that form the foundation of strength training.

Below are examples of exercises that combine core rigidity with a dynamic load (unilateral symmetrical bent row, highplank pull through).

It is important to note that although training bracing can be useful, it can also be redundant. The core’s bracing capacity is stimulated heavily in movements such as squats, hinges, and lunges (16,17). Theoretically, this could mean as one is able to load progressively heavier compound movements, challenging the core directly with bracing challenges can become progressively more redundant unless there is a specific reason to implement it.

Integrating The Basic Core Training Philosophy into Programming

To summarize what has been covered so far, a well-designed introductory program often has two broad categories of core work:

Direct Core Work

This includes exercises performed primarily to strengthen, activate, or grow the core musculature. These can be bodyweight exercises like crunches and lying leg raises, side-plank hip dips, or weighted exercises like cable crunches, weighted sit-ups, hanging leg raises, or machine-based abdominal work. Although it’s important to remember that growing the core through exercise contributes negligibly to the appearance of the midsection compared to genetics, subcutaneous adiposity, and progressive, whole-body strength training.

One should be conscious that placing a direct core movement and training it near failure before any other compound lift that involves the core might make it less productive during the subsequent compound lift.

Below are some exercises that within this framework, could be considered ‘direct core work’ (lying leg raise, decline sit up with a unilateral load, 45 degree side bend).

Integrated and Skill-Transfer Work

These are the exercises that target the core’s primary roles: stabilization, resisting motion, and force transfer. Examples include bodyweight exercises like plank variations, dead bugs, bird dogs, Pallof presses, carries, unilateral rows, asymmetrically loaded lunges, offset squats, etc. Many of these you have already seen previously mentioned. These should be the foundation of an effective core training program for someone learning how to carry their core training into compound movements.

Small changes to existing compound movements can dramatically increase core demand. For example, loading one side instead of two or changing stances can both create meaningful trunk challenges without adding entirely new exercises.

These movements don’t only train the core to maintain rigidity but train it to do so while load moves and body position changes. It also allows the development of more advanced proprioception by utilizing movements that differentiate trunk motion from larger joint motion. Take for example, a hip airplane. This is a very powerful exercise for the hips that requires trunk rigidity and motion around the hip joint. Without an understanding of how to differentiate those two aspects of movement, hip airplanes become much more difficult to perform.

Beyond The Basics: Spinal Motion

So far, this blog has covered core training from basic aesthetic-driven workouts to more practical and functional ways of training the core’s role in movement. By learning basic bracing and advanced proprioceptive concepts such as maintaining trunk rigidity while accessing motion from other joints, this blog has provided an applicable foundation to core training.

Although these topics are foundational to understanding and training the core and have many practical implications for beginner, intermediate, and even advanced trainees, they miss an ongoing discussion around core training that is more relevant for the performance of athletes, those trying to reduce injury risk, or those who wish to optimize their spine and core’s function. That discussion is whether or not to load the spine during movement.

Research on loading spinal motion shows conflicting ideas: historically, studies suggested loading spinal flexion increases injury risk and contributes to a subsequent reduction in load tolerance, while other clinical evidence finds no strong link between spinal flexion during lifting and low back pain onset, and some studies even finding that training isolated low-back flexion is advantageous for strength over time. A lot of researchers agree that spinal structures like discs don’t adapt like other joints, and that excessive motion can damage them, but avoiding them all together may be impossible, and there is some evidence to show they may adapt to loading. These conflicting narratives create a divide in the recommendations and dogma of many coaches (18,19, 20). This has led to the recent resurgence of movements such as Jefferson curls, side bends, and Zecher squats/deadlifts, movements that load the spine in motion (especially flexion).

Below are movements that load the spine in deep flexion ranges, with high axial load (jefferson curl, zercher deadlift).

I could go on and on with studies from one side or the other, listing them out until your brain goes numb. But you aren’t hear to listen to the details of a bunch of RCTs, you’re here to get my consolidated review. It is my belief that this type of core training that is built on accepting spinal motion and loading it intentionally has benefits for some, but mainly after the foundational principles that govern well-designed core training are established. Spinal discs likely adapt, but slower than other body structures. Deep, repetitive flexion with heavy loads will likely damage the discs of some. Therefore, loading in deep flexion, extension, or lateral flexion with axial load requires special caution with progression and load management. I personally include loaded purposeful spinal motion movements after my heavy lifting with a neutral spine is complete, albeit infrequently and with <15% of my typical static loads.

Beyond The Basics: Rotational Force

For athletes, recent research has emphasized that measures of athletic capacity are improved most by good strength training consisting of basic compounds adjunct to sport-specific work rather than just trying to recreate sport-skills in a gym setting (18,21,22,23,24). In fact, many believe recreating skills in a gym setting may be counterproductive to increasing skill in a competitive setting, as now the athlete is developing habits that aren’t practical for when they are performing their sport. Therefore, even for advanced athletes, building basic bracing and stability proprioception in the gym that will transfer best to movements like squats, deadlifts, presses, and pulls should preclude actively loading spinal motion for sport-specific movements. Most of the work that loads the core in sport-specific motion will come from field work for athletes.

However, there is a unique function of the core for athletes, and that's utilizing core motion during rotation or multiplanar movements to coordinate and create elastic force rather than restricting it to a rigid column. This allows athletes to create and experience much higher peak forces through movement. This may be applicable for athletes looking to improve rotational power through training, for example when in off season without much active field work. This is likely sport specific and there is also a need for research on core training and running, as direct core work may be associated with more trained rigidity, which may influence running mechanics (22, 23, 6).

Below are three movements that include force transmission performed by the core, with progressining elasticities (rigid horizontal rotation, elastic whole body rotation, kettlebell pendullum golf swing). A more elastic, less rigid core allows for higher peak forces.

I personally believe it would be most practical for athletes to develop rotational power through practicing whatever rotation-based sport they’re engaging in, while having a foundational adjunct strength-training program that includes accessories that develop the core’s sport-specific function when field work is insufficient.

Currently, the body of evidence surrounding whether to resist spine motion or accept it is too divisive to conclude in sport and injury prevention. Likely, that conclusion will differ if you are an athlete in your early 20s looking to improve your drive for professional golf, compared to someone in their late 70s at high risk of vertebral fractures looking to build bone mineral density. If you are at a low risk of injury, it is likely beneficial to train spinal motion, rotation, and stability. If it doesn’t create pain, uses manageable but challenging loads, and is within realistic and safe domains, then loading spinal flexion and rotation may benefit your goals.

Integrating Advanced Core Training Philosophy Into Programming

Once someone has developed a foundation of trunk control, bracing, and integrated stability, more advanced forms of core training can be layered into a program. This does not replace the foundational elements discussed earlier, it builds on them.

A helpful way to think about this is along a learning continuum.

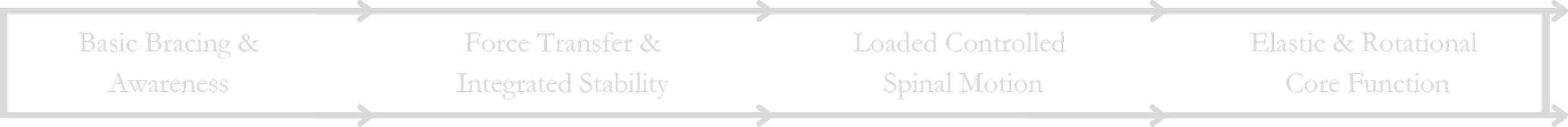

The Core Training Learning Continuum

This diagram represents how the core training toolkit can develop over time:

Early stages focus on learning how to create trunk stiffness and maintain position. Most beginners and many intermediate lifters will benefit most from mastering this stage and moving into integrated stability and force transfer.

The focus then shifts toward maintaining trunk integrity while the limbs move and external loads increase in the main compound lifts. This is where carries, unilateral work, and asymmetrical loading variations help bridge isolated core control into compound lifting. Athletes can also spend time most of their time in this stage while integrating elastic and rotational core function from field work.

Once an individual demonstrates the ability to stabilize effectively under meaningful load, masters proprioception, and reduces their risk of injury it may be advantageous to explore controlled spinal motion under significant load. At this stage, spinal movement is not introduced as a replacement for stability, but as an added capacity. Exercises that involve loaded flexion, extension, lateral flexion, or rotation can improve tissue tolerance, motor control through range, and confidence in positions that daily life and sport may require anyway.

At the far end of the continuum is the most sport-specific expression of core function: coordinating trunk stiffness and motion dynamically to create and transfer force. This is particularly relevant for athletes involved in sprinting, throwing, striking, and change-of-direction sports, where the trunk must alternate between acting as a rigid transmitter of force and a mobile contributor to elastic energy.

How Core Training Methods Fit Together

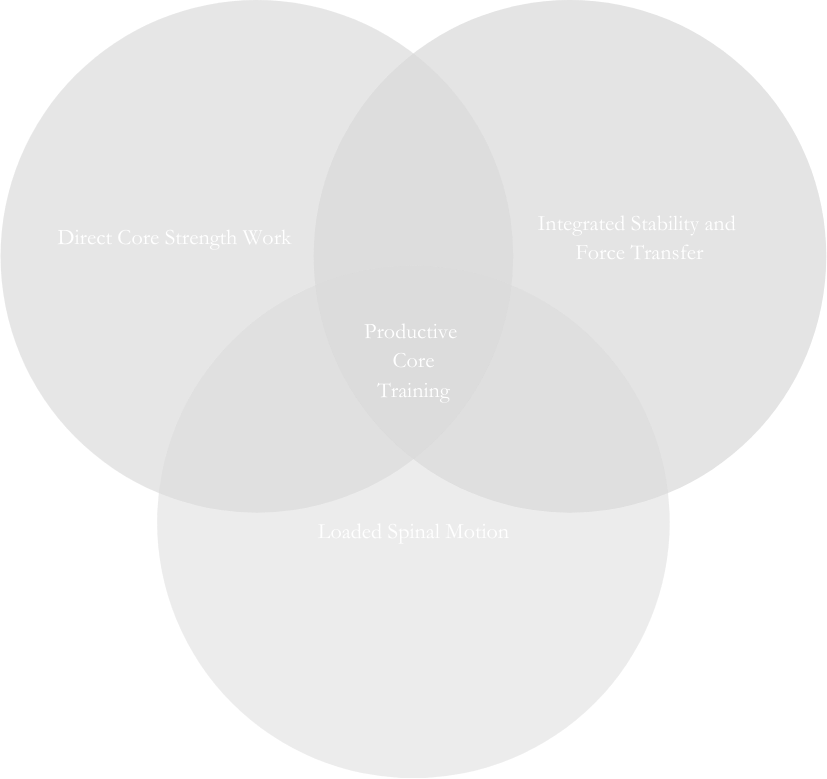

Once the continuum has been fulfilled and someone has learned all aspects of core training, rather than viewing core training as separate camps, it is more useful to see different methods as overlapping tools within a program.

This diagram can be visualized as three intersecting circles:

Direct Core Strength Work

Exercises that primarily load the trunk musculature through flexion, extension, or anti-movement demands (e.g., crunch variations, back extensions, hanging leg raises).

Integrated Stability & Force Transfer Work

Exercises where the trunk’s role is to resist motion while force is produced elsewhere (e.g., compounds, carries, Pallof presses, unilateral rows, offset squats, asymmetrical lunges).

Loaded Spinal Motion Work

Exercises where the spine intentionally moves under load in a controlled manner (e.g., Jefferson curls, side bends, rotational cable work, controlled spinal flexion or extension drills).

Where these categories overlap is where much of productive training occurs. For example, many compound lifts already train integrated stability and force transfer. Adding direct trunk work can improve strength endurance that supports those lifts. Some direct core strengthening also blends spinal motion. Introducing carefully dosed spinal motion work can expand the range of positions the trunk can tolerate.

The goal is not to maximize all three at once, but to emphasize the methods that best match the individual’s training age, goals, and injury risk.

Eight Practical Takeaways

Okay, that was a lot. Let’s sum it up.

Effective core training is not flashy. It does not rely on a burning sensation or moral pressure. It relies on the same principles that govern all successful training: progressive overload, specificity, sufficient effort, and intelligent exercise selection.

Train the core directly if your goal is strength or hypertrophy. Integrate it if your goal is proprioception and bracing. Ideally, do both. Train it statically, and train it dynamically. Ideally, do both.

Avoid programs that promise aesthetic outcomes through isolated exercises alone and be skeptical of any approach that prioritizes discomfort over adaptation. What you’ll do and enjoy safely is more important than what's best.

Bodyweight core exercises are not inherently inferior; their effectiveness depends on progressions, intent, and the experience of the person doing them.

Intentional loading and the acceptance of spinal motion as a part of movement is likely useful when selecting exercises that challenge and progress movement rather than strictly avoiding spinal motion to the point of it hindering practical improvement.

Core training exists on a continuum of knowledge, exercises, and adaptation. This continuum is heavily intertwined with individual context. A young athlete will likely benefit from training much differently than an untrained senior. Accepting this contextual reliance is foundational to relinquish any authoritative core-training dogma.

When trained with intention and context, the core becomes what it is meant to be: a strong and adaptable system that supports both performance and long-term health.

Conclusion

I hope this blog helped you both deconstruct, and reconstruct some of the thoughts you had around training the core. One of the best ways to consolidate learning is to engage and challenge ideas. So, if you have your own thoughts around core training or think I missed something, feel free to leave a comment below! No way of thinking about training can be perfect, and that’s okay; take from this what will help you and leave with it what won’t. There are many ways to think about training and this is how I conceptualize this topic in my own programming, and when working with clients. Have fun training!

References

Sannasi R, Dakshinamurthy A, Dommerholt J, Desai V, Kumar A, Sugavanam T. Diaphragm and core stabilization exercises in low back pain: A narrative review. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2023 Oct;36:221‑7. doi:10.1016/j.jbmt.2023.07.008. Epub 2023 Jul 13. PMID:37949564.

Mantilla Toloza SC, Villareal Cogollo AF, Peña García KM. Pelvic floor training to prevent stress urinary incontinence: A systematic review. Actas Urol Esp (Engl Ed). 2024 May;48(4):319‑27. doi:10.1016/j.acuroe.2024.01.007. Epub 2024 Mar 29. PMID:38556125.

Manzotti A, Fumagalli S, Zanini S, Brembilla V, Alberti A, Magli I, et al. What is known about changes in pelvic floor muscle strength and tone in women during the childbirth pathway? A scoping review. Eur J Midwifery. 2024 Aug 2;8. doi:10.18332/ejm/189955. PMID:39099673; PMCID:PMC11295251.

Okada T, Huxel KC, Nesser TW. Relationship between core stability, functional movement, and performance. J Strength Cond Res. 2011 Jan;25(1):252‑61. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181b22b3e. PMID:20179652.

Guo XB, Lan Q, Ding J, Tang L, Yang M. Effects of different types of core training on pain and functional status in patients with chronic nonspecific low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Physiol. 2025 Oct 16;16:1672010. doi:10.3389/fphys.2025.1672010. PMID:41178988; PMCID:PMC12571568.

Lupowitz LG. Comprehensive approach to core training in sports physical therapy: optimizing performance and minimizing injuries. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2023 Aug 2;18(4):800‑6. doi:10.26603/001c.84525. PMID:37547832; PMCID:PMC10399110.

Ross R, Neeland IJ, Yamashita S, Shai I, Seidell J, Magni P, et al. Waist circumference as a vital sign in clinical practice: a Consensus Statement from the IAS and ICCR Working Group on Visceral Obesity. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020 Mar;16(3):177‑89. doi:10.1038/s41574‑019‑0310‑7. Epub 2020 Feb 4. PMID:32020062; PMCID:PMC7027970.

Jayedi A, Soltani S, Zargar MS, Khan TA, Shab‑Bidar S. Central fatness and risk of all cause mortality: systematic review and dose‑response meta‑analysis of 72 prospective cohort studies. BMJ. 2020 Sep 23;370:m3324. doi:10.1136/bmj.m3324. PMID:32967840; PMCID:PMC7509947.

Visser M, Sääksjärvi K, Burchell GL, Schaap LA. The association between muscle mass and change in physical functioning in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur Geriatr Med. 2025 Oct;16(5):1731‑48. doi:10.1007/s41999‑025‑01230‑y. Epub 2025 May 23. PMID:40407980; PMCID:PMC12528211.

Hansen GT, Sobreira DR, Weber ZT, et al. Genetics of sexually dimorphic adipose distribution in humans. Nat Genet. 2023;55:461‑70. doi:10.1038/s41588‑023‑01306‑0.

Radziszewska M, Ostrowska L, Smarkusz‑Zarzecka J. The impact of gastrointestinal hormones on human adipose tissue function. Nutrients. 2024 Sep 25;16(19):3245. doi:10.3390/nu16193245. PMID:39408213; PMCID:PMC11479152.

Li J, Liu X, Yang Q, Huang W, Nie Z, Wang Y. Low lean mass and all‑cause mortality risk in the middle‑aged and older population: a dose‑response meta‑analysis of prospective cohort studies. Front Med (Lausanne). 2025 Jun 25;12:1589888. doi:10.3389/fmed.2025.1589888. PMID:40636391; PMCID:PMC12237975.

Schoenfeld BJ, Grgic J. Effects of range of motion on muscle development during resistance training interventions: a systematic review. SAGE Open Med. 2020 Jan 21;8:2050312120901559. doi:10.1177/2050312120901559. PMID:32030125; PMCID:PMC6977096.

Rosenfeldt M, Stien N, Behm DG, Saeterbakken AH, Andersen V. Comparison of resistance training vs static stretching on flexibility and maximal strength in healthy physically active adults: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil. 2024 Jun 28;16(1):142. doi:10.1186/s13102‑024‑00934‑1. PMID:38943165; PMCID:PMC11212372.

Saraceni N, Kent P, Ng L, Campbell A, Straker L, O’Sullivan P. To flex or not to flex? Is there a relationship between lumbar spine flexion during lifting and low back pain? A systematic review with meta‑analysis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2020 Mar;50(3):121‑30. doi:10.2519/jospt.2020.9218. Epub 2019 Nov 28. PMID:31775556.

Rodríguez‑Perea Á, Reyes‑Ferrada W, Jerez‑Mayorga D, Chirosa Ríos L, Van den Tillar R, Chirosa Ríos I, et al. Core training and performance: a systematic review with meta‑analysis. Biol Sport. 2023 Oct;40(4):975‑92. doi:10.5114/biolsport.2023.123319. Epub 2023 Feb 3. PMID:37867742; PMCID:PMC10588579.

van den Tillaar R, Saeterbakken AH. Comparison of core muscle activation between a prone bridge and 6‑RM back squats. J Hum Kinet. 2018 Jun 13;62:43‑53. doi:10.1515/hukin‑2017‑0176. PMID:29922376; PMCID:PMC6006542.

Steele J, Bruce‑Low S, Smith D, Osborne N, Thorkeldsen A. Can specific loading through exercise impart healing or regeneration of the intervertebral disc? Spine J. 2015 Oct 1;15(10):2117‑21. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2014.08.446. PMID:26409630.

Owen PJ, Hangai M, Kaneoka K, Rantalainen T, Belavy DL. Mechanical loading influences the lumbar intervertebral disc: a cross‑sectional study in 308 athletes and 71 controls. J Orthop Res. 2021;39:989‑97. doi:10.1002/jor.24809.

Fisher JP, Stuart C, Steele J, Gentil P, Giessing J. Heavier- and lighter-load isolated lumbar extension resistance training produce similar strength increases, but different perceptual responses, in healthy males and females. PeerJ. 2018;6:e6001. doi:10.7717/peerj.6001.

Makaruk H, Starzak M, Tarkowski P, Sadowski J, Winchester J. The effects of resistance training on sport‑specific performance of elite athletes: a systematic review with meta‑analysis. J Hum Kinet. 2024 Apr 15;91(Spec Issue):135‑55. doi:10.5114/jhk/185877. PMID:38689584; PMCID:PMC11057612.

Li G, Peng K. Core muscle training and its impact on athletes’ explosive power. Int J Public Health Med Res. 2024;1:88‑96. doi:10.62051/ijphmr.v1n3.13.

Keiner M, Kadlubowski B, Sander A, Hartmann H, Wirth K. Effects of 10 months of speed, functional, and traditional strength training on strength, linear sprint, change of direction, and jump performance in trained adolescent soccer players. J Strength Cond Res. 2022 Aug 1;36(8):2236‑46. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000003807. Epub 2020 Aug 27. PMID:32868678.

Zemková E. Perspective: a head‑to‑toe view on athletic locomotion with an emphasis on assessing core stability. Sports Med Health Sci. 2025. doi:10.1016/j.smhs.2025.07.001.